Authors: Arvind Agarwal, Ajay Raja

“I felt terrible that microcredit took this wrong turn,” Noble Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, the visionary behind the concept of Microfinance, has said.

Today, microfinancing is far from the vision of its inventor, who started the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in the 1980s to offer small loans to low-income individuals who do not qualify for bank loans. “The concept of microcredit was abused by some and turned into profit-making enterprises for owners of microcredit institutions. Many went in the inevitable direction of loan-sharking,” he says.

According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), microfinance is a collateral-free loan given to a household with an annual income of up to INR 3 lakhs. For a company to qualify as a Non-Banking Financial Company – Micro-Finance Institution (NBFC-MFI), an NBFC should hold 75% of such loans in its books. As of March 2024, NBFC-MFIs in India command a market share of 40% of the microfinance AUM, and the total industry portfolio outstanding was INR 4,33,697 Crores.

Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) facilitate access to formal loans to individuals from informal sectors who often lack proper documentation and would otherwise be forced to turn to loan sharks for their financial needs. The availability of formal financing at affordable interest rates helps these people take a step towards economic growth and self-sufficiency.

However, the present landscape of microcredit suggests that microfinancing is yet to realize fully its intended goals.

Pricing Amendments

Earlier, RBI regulations allowed NBFC-MFIs to set interest rates to the lower of (a) Cost of Funds + 10% (loan portfolios exceeding INR 100 Crores) /12% (Other MFIs), or (b) 2.75x of the average base rate of the five largest commercial banks.

Then, during the pandemic, in an effort to stimulate the struggling economy, the central government reduced the base rates of banks, leading to a decreased pricing level of MFIs as per clause (b). Additionally, the cost of funds shot up due to elevated pandemic-related provisioning. Evidently, these changes impacted the MFI businesses.

Therefore, in March 2022, RBI decided to allow MFIs to tailor loan pricing based on the borrower’s credit risk profile in alignment with the lending framework of other financial entities. RBI eliminated the cap on interest rates previously imposed on MFIs and asserted that the interest rates should not be usurious. The regulatory body emphasized that MFIs must formulate a Board-approved policy for their loan pricing with comprehensive and well-documented interest rate models, including factors like cost of funds, risk premium, margin, etc.

However, the observed outcomes did not align with the intended objectives.

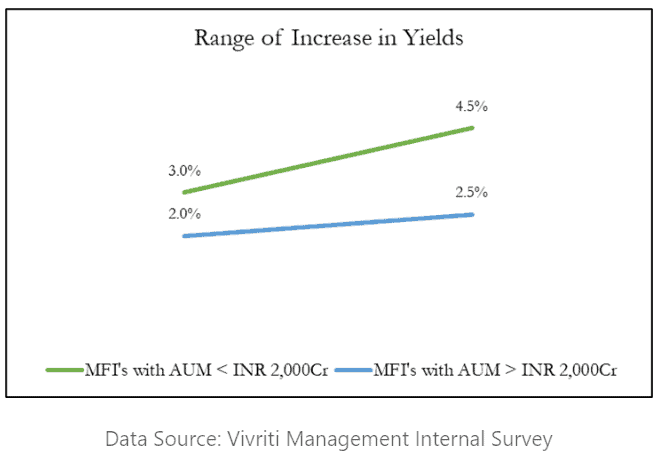

According to a Vivriti Asset Management survey, most MFIs have raised rates uniformly, regardless of varying risks associated with customers and geographical locations. The graph below illustrates the rate adjustments:

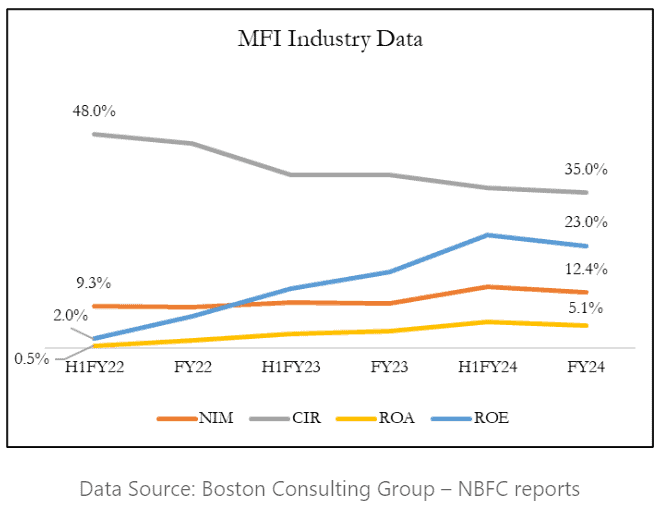

Consequently, there was a steady increase in Net Interest Margin (NIM), Return on Assets (ROA), and Return on Equity (ROE), and a decrease in Cost-to-Income Ratios (CIR). This demonstrated encouraging trends for the industry, but the critical inquiry revolves around one question — at whose expense?

In FY2024, the ROA and NIM of the NBFC-MFIs increased by 218.8% and 36.3%, respectively, compared to FY2022. In contrast, during the same period, Diversified NBFCs (excluding Housing Finance Companies and Gold NBFCs) experienced more modest growth in ROA and NIM, at 40.9% and 4.0%, respectively. Notably, the loan book growth for the same period for MFIs and Diversified NBFCs is around 52%.

It is understandable that MFIs operate with a higher risk, but the 9x increase in NIM post-amendment raises concerns about the ethical considerations of the MFIs.

RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das has cautioned NBFC-MFIs to exercise prudence in utilizing the flexibility of interest rates, emphasizing the importance of considering borrowers’ affordability and repayment capacity. RBI’s nudge is slowly prompting most MFIs to reduce interest rates, making their products more affordable for borrowers. We need to wait to see how this will transform and positively affect the borrowers in the coming quarters.

Operational Indiscipline

“Heated districts” are areas with more than ten operational MFIs within a single district. In recent times, there has been an increase in heated districts across India, which has led to numerous frauds in the sector, driven by the pressure for growth that exceeds sustainable levels.

The original purpose of microfinance was to provide loans to individuals to expand small businesses and sustain their households. Today, it has evolved into a concept where loans are extended for all purposes, including personal expenses, consumer purchases, and even settling existing debts.

Since borrowers were not utilizing the loans for income-generating activities, they have been found to be taking additional loans to repay existing ones. This perpetuates a continuous cycle of evergreening, contributing to a situation where the livelihoods of the borrowers remain stagnant and fail to see significant improvement.

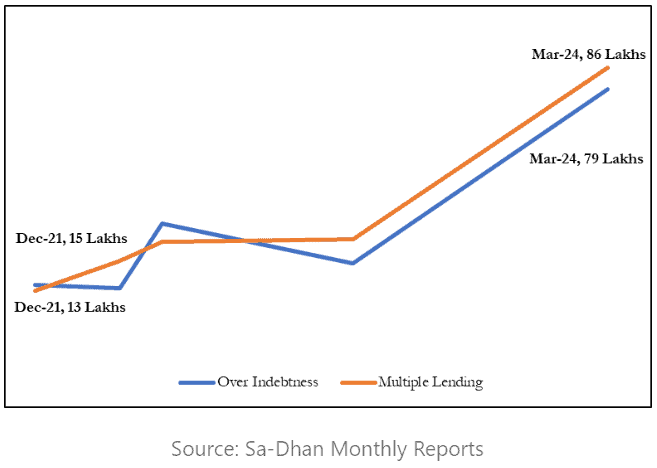

A monthly district-level analysis by Sa-Dhan, an association of Microfinance and Impact Finance Institutions and an RBI-appointed self-regulatory organization, provides two critical metrics:

The analysis reveals alarming trends in over-indebtedness and multiple lending. Over-indebted unique borrowers surged ~427% between December 2021 and March 2024. Similarly, unique borrowers under the Multiple Lending categories spiked ~562% in the same period. It is also to be noted that the increase in unique borrowers during the same period is around ~ 39% only.

By March 2024, 166 districts had multiple lending levels above 15%, compared to none in December 2021. Even before the pandemic, only 69 districts had rates above 10% in December 2019. Over-indebtedness levels above 15% were found in 120 districts by March 2024, up from just 18 districts with levels above 10% in December 2021.

To put things in perspective, around 21% of districts in India have multiple lending levels above 15%, and around 15% of districts in India have over-indebtedness levels above 15%. This dramatic rise in borrower debt and multiple lending highlights the urgent need for interventions to mitigate financial strain and promote sustainable lending practices in the microfinance sector.

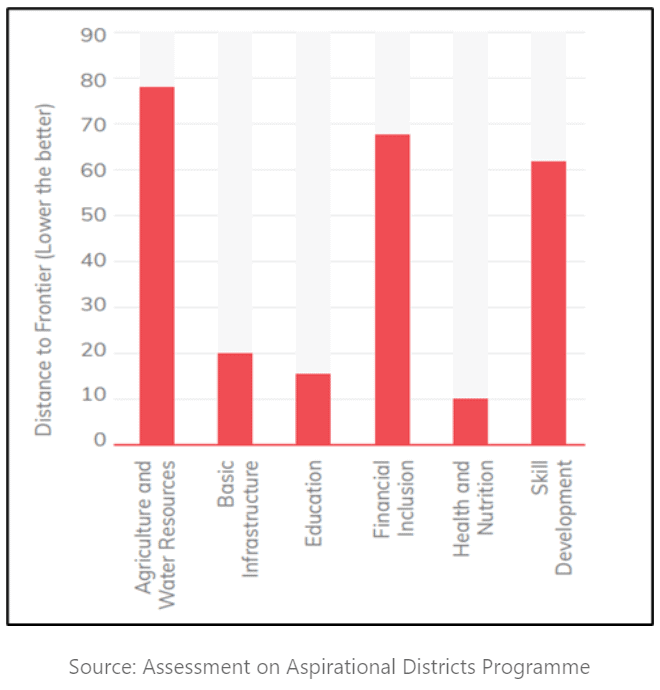

Another crucial consideration is the impact of MFIs on “aspirational districts”. In January 2018, PM Narendra Modi launched the Aspirational Districts Programme, which aims to quickly and effectively transform the 112 most under-developed districts across the country. The program measures the progress by ranking based on the incremental progress made across 49 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) under five broad socio-economic themes – Health & Nutrition, Education, Agriculture & Water Resources, Financial Inclusion, & Skill Development and Infrastructure.

Based on the programme’s report, financial inclusion remains a primary focus for the majority of aspirational districts, as their average scores are significantly distant from the frontier. The average district-level (country-level) penetration has increased to 18.7% as of March 2024, up from 16.2% in December 2021. Similarly, the penetration in aspirational districts has risen from 16.6% to 18.9%.

The progress is at par in both regions. However, we strongly believe that the focus and penetration levels should be significantly higher for aspirational districts to foster overall district improvement. Lack of aggressive approach might signal that the lenders are playing safer and deploying funds to already overheated districts rather than much-needed aspirational districts.

Profits over purpose?

Originally intended to uplift the underserved by providing accessible credit, MFIs did pull households out of poverty. However, over the past few years, they seem to have increasingly strayed into only profit-driven practices, often at the expense of their vulnerable clientele.

The concentration of MFIs in already saturated areas rather than focusing on aspirational districts reveals a prioritization of profitability over genuine socio-economic development. The surge in interest rates, coupled with issues of over-indebtedness and multiple lending, underscores a departure from their foundational goals.

While MFIs have undoubtedly benefited people, their evolving practices do raise ethical concerns, suggesting that they are beginning to hurt more than they benefit the underserved communities.

Regulations that effectively curb both over-indebtedness and multiple lending, and bring the cost of borrowing down for end-clients are the need of the hour. In our opinion, a pro-active well-organized board with strong governance practices can safeguard against the pitfalls of MFIs, while minimizing harm and aligning with their mission to empower underserved communities they were designed to support.